When Comics Think in Shots and Silence: Ifeoluwa Owoade on Cinema, academia, and Hounds and Jackals

12 Feb 2026

Exclusive

Recent Posts

When Comics Think in Shots and Silence: Ifeoluwa Owoade on Cinema, academia, and Hounds and Jackals

12 Feb 2026

Afro Women in Animation Festival Returns in 2026 with Virtual Workshops Ahead of Lagos Main Event

10 Feb 2026

“Nigeria Cannot Survive on Music, Movies, and Fashion Alone” - Tunji Anjorin on Building Cultural Infrastructure in a Hype Economy

6 Feb 2026

Neurodiverse Creators Lab Kicks Off with Strong Start, Empowering Youth Through Creativity and Digital Skills

4 Feb 2026

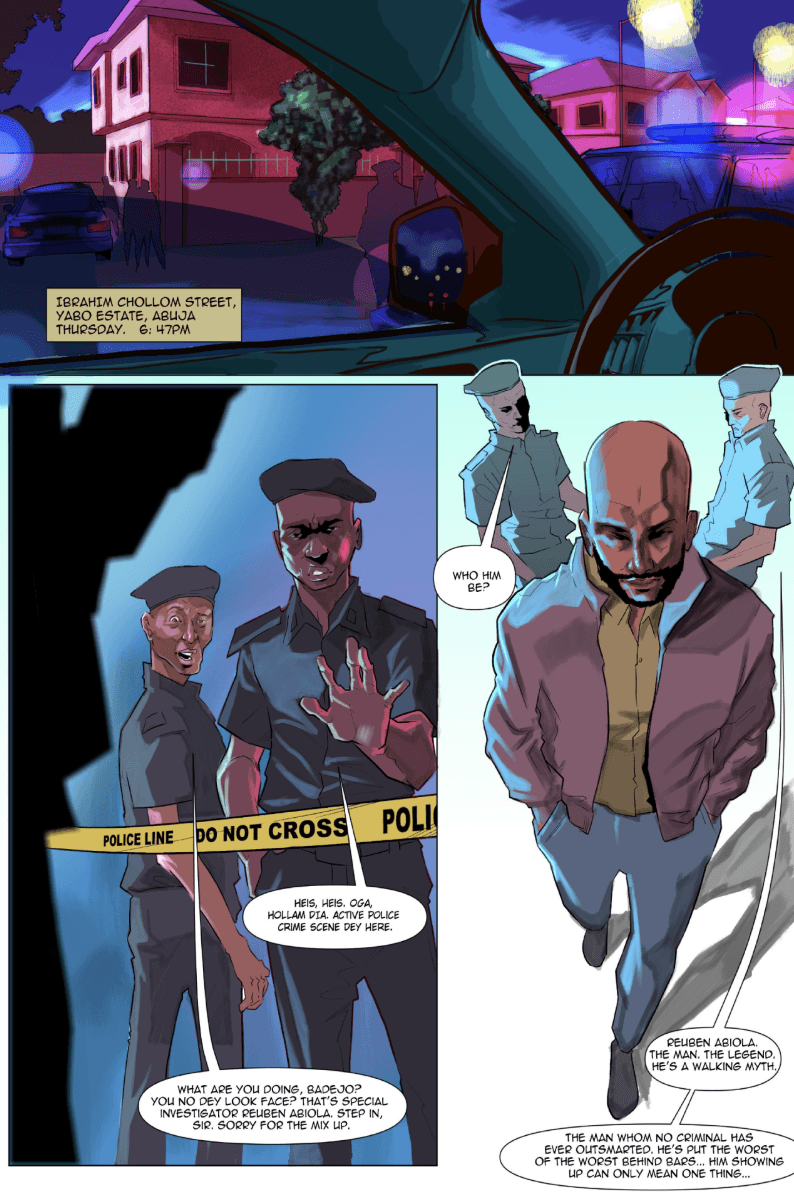

Canvas of the Macabre: Theology, Crime, and Visual Discipline in Hounds and Jackals

2 Feb 2026

Teased and released in the final quarter of 2025, Ifeoluwa Owoade’s, Hounds and Jackals did not begin as a comic book problem. It began as a film problem.

“When I created Hounds and Jackals, one of the replies I got from people who read it was that it felt very cinematic,” he says. “And I think I’m very pleased with that review, because that was one of the major things I was trying to achieve.”

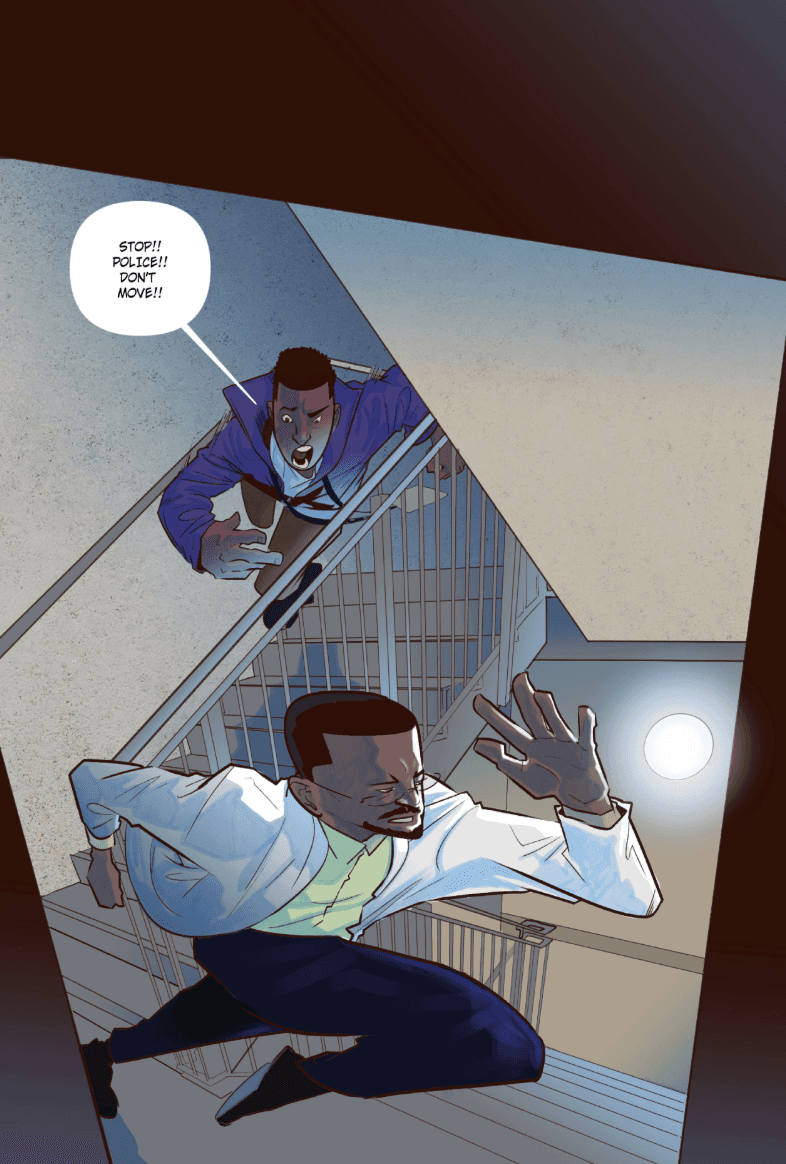

That reaction was not accidental. From the outset, Owoade revealed in an interview with TheACE that he was less interested in producing a conventional comic-reading experience than in constructing something that behaved like cinema on the page. “I wanted to create a comic book experience that transcends the medium,” he explains, “not just reading a comic book and you feel, ‘oh, this is just a comic book’. I wanted to make readers read a comic book that plays like a movie in your mind.”

This ambition to make still images move in the reader’s imagination became the organising principle of Hounds and Jackals. Owoade describes his process plainly: “I don’t think about the comic book like I want to create a comic book. I think about it like I want to make a movie.”

From that decision flows everything else. Panels are treated as shots. Dialogue is written to carry subtext the way film conversations do. Backstories are not announced but inferred. “If I was making a movie of this, how would the shots be? How would the conversations be? How would we get to know character backstories just from their conversations, the way they are discussing?” he asks. “There’s a lot that we might not have shown in the book, but from their discussions and from the way they interacted… you’re able to get an insight into the character.”

This cinematic thinking also explains the density of the work. Hounds and Jackals is designed to reward rereading. “I went big on visual metaphors,” Owoade says, noting that many of them are easy to miss on a first pass. “There are some movies like that when you watch them the first time, there are interesting details you might miss. Then when you give it a second watch or a third watch, that’s when you understand it better.”

The same logic applies to the comic. “Reading the comic for the first time, you might not get everything that is going on. But if you give it a second read or a third read, everything starts to piece itself together.” Even for its creator, the work continues to reveal itself. “I read the book again recently, and I even discovered new things that I didn’t discover the first time I read it,” he admits. “Some of these conversations have new meanings… deeper meanings than what we intended.”

That layered approach to storytelling reflects not just Owoade’s love of cinema, but his academic sensibility, an aspect of his journey that often surprises people encountering his work for the first time.

“When I studied fine arts in school, at some point I thought I was going to go into the academic side of it actually,” he says. “As much as I love the practicals of it, I also love the academic part of it as well.”

For several years, that path felt entirely plausible. After graduating, Owoade did not immediately plunge into studio practice. Instead, he taught fine arts, spending “two, three years” in the classroom. His experience there sharpened his critical instincts. The curriculum, he recalls, felt “limited” and “restricting”, frozen in an earlier era while the world moved on.

Rather than accept that stagnation, he experimented. “I tried to be innovative,” he says. “I didn’t restrict my students to the curriculum.” He introduced animation, digital tools, and software like Photoshop, interventions that blurred the line between theory and practice.

That impulse to question structure, to rethink how knowledge is transmitted, never left him. Eventually, however, Owoade reached a turning point. “I guess it was just me making the decision that my time in academia has matured into what I wanted, and I wanted to now go full time practicing,” he reflects.

The move into professional practice, including his work at Symphonii Studios, gave him a different kind of freedom: the space to pursue a personal project without compromise. Hounds and Jackals emerged from that freedom, shaped by years of teaching, thinking, analysing, and watching films.

The result is a psychological crime narrative that is as much about ideas as it is about plot. At its core, Owoade says, the book is an exploration of death and truth. “We live in a postmodern era whereby we have relative interpretations of truth,” he explains. “All the characters involved in the case had different ways of viewing the truth and different approaches to how they were looking for the solution.”

Even the visual structure of the comic participates in this inquiry. In later chapters, Owoade embeds a critique of the criminal justice system through imagery rather than exposition. “There were some panels… where you could see the flag of Nigeria that makes up the panel,” he notes. “Each character is on either side of the flag… everybody maintaining different viewpoints, different perspectives of the truth they are uncovering.”

This commitment to subtext, metaphor, and rereadability is also why Owoade chose to work alone on the project; writing, drawing, colouring, and lettering it himself. While that would overwhelm many creators, he describes the experience almost casually. “One would think that would be overwhelming, but it wasn’t overwhelming for some reason,” he says. “Maybe because I enjoyed working on it so much.”

In the end, Hounds and Jackals stands as a work shaped by dual impulses: the rigour of an academic mind and the instincts of a filmmaker. Owoade’s journey suggests that these impulses are not opposites, but complements. His time in academia trained him to interrogate systems, question assumptions, and think structurally. His love of cinema taught him how to make those ideas felt.

“I wanted to make readers read a comic book that plays like a movie in your mind,” he says again, almost as a refrain.

With Hounds and Jackals, he has done precisely that, crafting a comic that does not simply ask to be read, but to be watched, revisited, and thought through, long after the final panel.

Read our critique of Hounds and Jackals before the interview.

--------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------

AI Use at TheACE

TheACE uses artificial intelligence tools to support research, drafting and analysis across Africa’s creative industries. All content is verified, edited and approved by our human editorial team to ensure accuracy, clarity and responsible storytelling. AI assists our work; it does not replace human judgment.