“Nigeria Cannot Survive on Music, Movies, and Fashion Alone” - Tunji Anjorin on Building Cultural Infrastructure in a Hype Economy

6 Feb 2026

Exclusive

Recent Posts

“Nigeria Cannot Survive on Music, Movies, and Fashion Alone” - Tunji Anjorin on Building Cultural Infrastructure in a Hype Economy

6 Feb 2026

Neurodiverse Creators Lab Kicks Off with Strong Start, Empowering Youth Through Creativity and Digital Skills

4 Feb 2026

Canvas of the Macabre: Theology, Crime, and Visual Discipline in Hounds and Jackals

2 Feb 2026

Editorial: The Nigerian Comic Industry Finally Has a Reference Point — The Bookause 2025 Report

30 Jan 2026

Nigeria’s Comic Industry Runs on Talent and Momentum, Not Systems and Structure, and That Is the Problem

28 Jan 2026

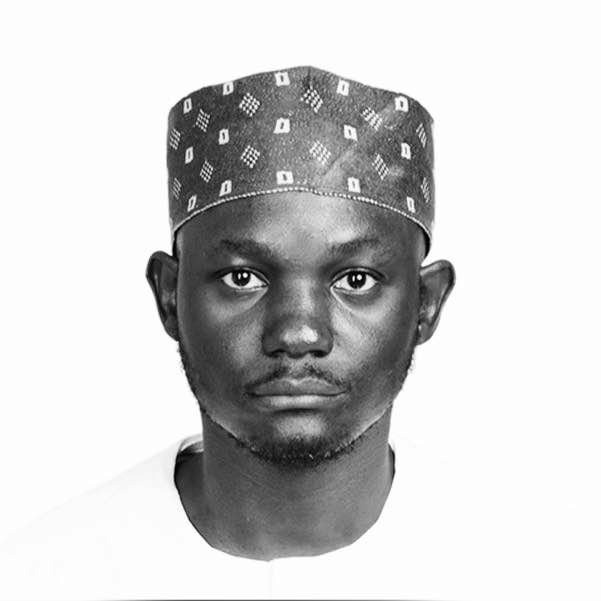

Tunji Anjorin is not in a hurry.

In an ecosystem obsessed with speed, viral launches, fast funding, and algorithmic relevance, the founder of Panaramic Entertainment has spent nearly two decades doing something quietly defiant: building slowly. Not towards spectacle or moments, but towards continuity and systems.

This is an unusual posture in Nigeria’s creative economy, where success is often measured in immediate visibility. Streams. Numbers. Reach. Tunji speaks instead in longer units of time. In books. In archives. In cultural memory. His concern is not what trends today, but what survives tomorrow.

“Nigeria cannot survive on music, movies, and fashion alone,” he says at one point during our conversation. “Only two fingers cannot do the work of ten.”

The metaphor is simple, but the implication is expansive. For all the global attention Nigerian music and film enjoy, Tunji believes the country’s creative ecosystem is structurally incomplete. Some sectors burn brightly, while others like comics, books, publishing, and historical storytelling, are treated as optional, even expendable. Yet these are the sectors that quietly sustain culture long after the spotlight moves on.

Firewood, Not Fireworks

For Tunji, comics are not side projects. They are infrastructure.

“If you don’t have books and comic books,” he explains, “you don’t have an unlimited source of firewood to keep the fire going.”

It is a telling image. Fireworks dazzle briefly; firewood keeps a home warm through the night. Tunji’s work at Panaramic has always leaned towards the latter. From its earliest projects, the studio has treated comics not merely as entertainment, but as vessels for cultural preservation, slow-burning artefacts designed to be returned to, shared, and remembered.

This approach has required patience, especially in a market that often questions the commercial viability of comics. There is a persistent assumption that Nigerians do not read, an idea Tunji rejects outright.

“Nigerians read,” he says simply. “The problem is access and visibility.”

For him, the issue has never been appetite, but infrastructure: distribution channels, cultural education, and the steady erosion of reading culture in the absence of sustained investment. Comics, he argues, are uniquely positioned to bridge that gap, visual enough to attract new readers, substantive enough to deepen engagement.

Where African Stories Begin

At the philosophical core of Panaramic’s work lies a refusal; the rejection of the idea that African culture meaningfully begins at the point of enslavement.

“We are told African culture starts at the point of enslavement,” Tunji says. “That is not the truth.”

It is a statement he delivers without flourish, but its weight is unmistakable. For Tunji, this framing is not merely historically incomplete; it is strategically damaging. It compresses centuries of precolonial history, governance, philosophy, and artistic expression into a single traumatic reference point, leaving little room for Africans to define themselves outside narratives of loss.

Panaramic’s historical comics are shaped by this conviction. Tunji is careful not to present them as authoritative retellings of history. That, he insists, is not their role.

“We are not telling the full truth of history,” he explains. “What we are doing is opening the door, so people can want to learn more.”

In this sense, Panaramic’s comics function less as conclusions and more as invitations. They do not claim to resolve historical debates; they provoke curiosity. They encourage readers to ask questions, to search further, to reconnect with stories that were prematurely closed.

Building Without Permission

This long-term thinking has not always aligned neatly with global creative platforms or distribution systems. Like many African comic publishers, Panaramic has had to navigate an industry largely designed around Western content assumptions, from genre expectations to audience profiling.

At one point, this friction became explicit. Panaramic’s work was submitted to Comixology, then one of the most visible global digital comic platforms. The rejection was not framed around quality, but around fit. African historical comics, it seemed, did not sit comfortably within pre-existing marketplace categories.

Rather than treat this as a failure, Tunji read it as a signal.

The issue, he realised, was not that the stories lacked value, it was that the platforms had been built with a different cultural centre of gravity. African stories were being assessed through frameworks never designed to hold them. Instead of reshaping the work to suit external validation, Panaramic continued building on its own terms.

Over time, a different pattern began to emerge; consistent interest from the African diaspora.

Orders increasingly came from outside Nigeria, particularly from readers in the United States and the United Kingdom, many of whom were searching for cultural reconnection rather than novelty. In one notable case, Panaramic’s work found its way into an American college, where it was adopted as part of the institution’s educational curriculum.

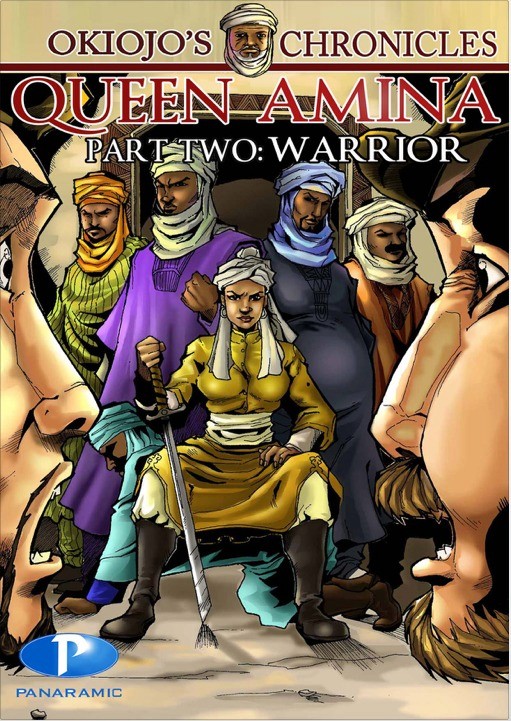

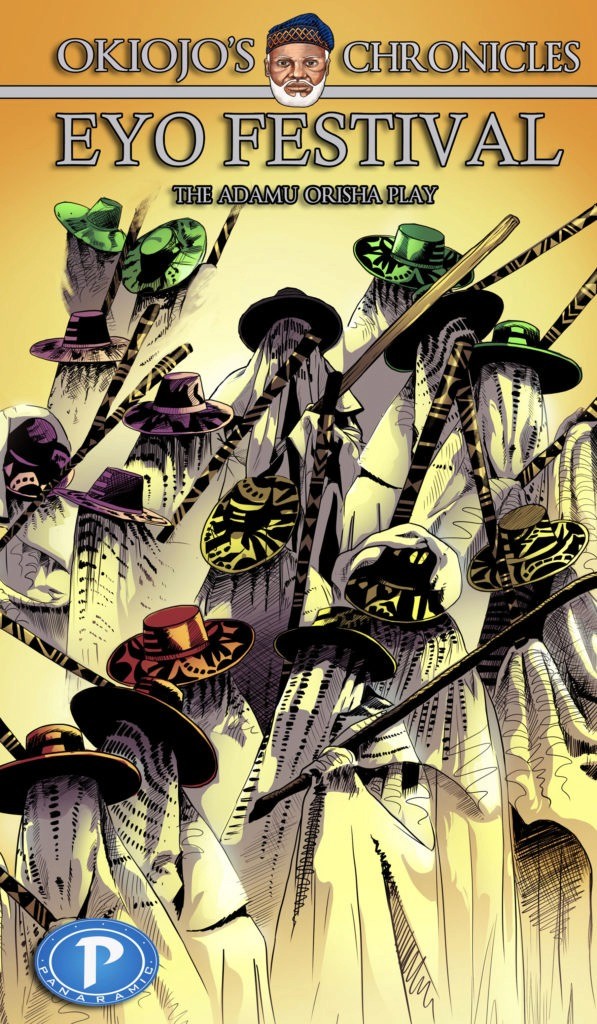

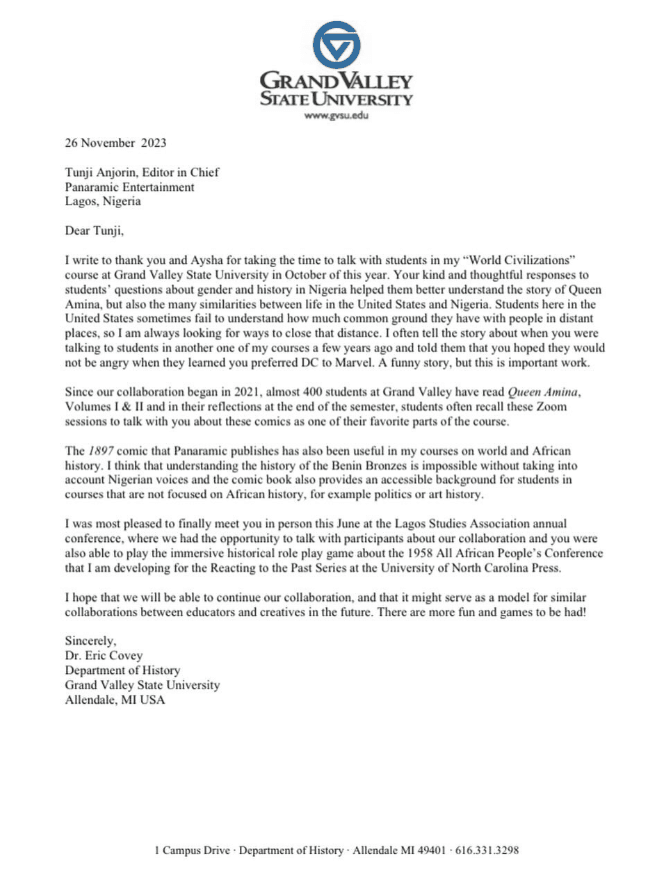

That engagement later extended beyond informal readership. In November 2023, Grand Valley State University formally acknowledged Panaramic’s comics as part of its World Civilisations curriculum, with nearly 400 students engaging the work across multiple semesters. For Tunji, this moment was quietly affirming. It demonstrated that African comics were not only viable as entertainment, but valuable as educational material, capable of entering classrooms, shaping discourse, and standing alongside more traditional academic texts.

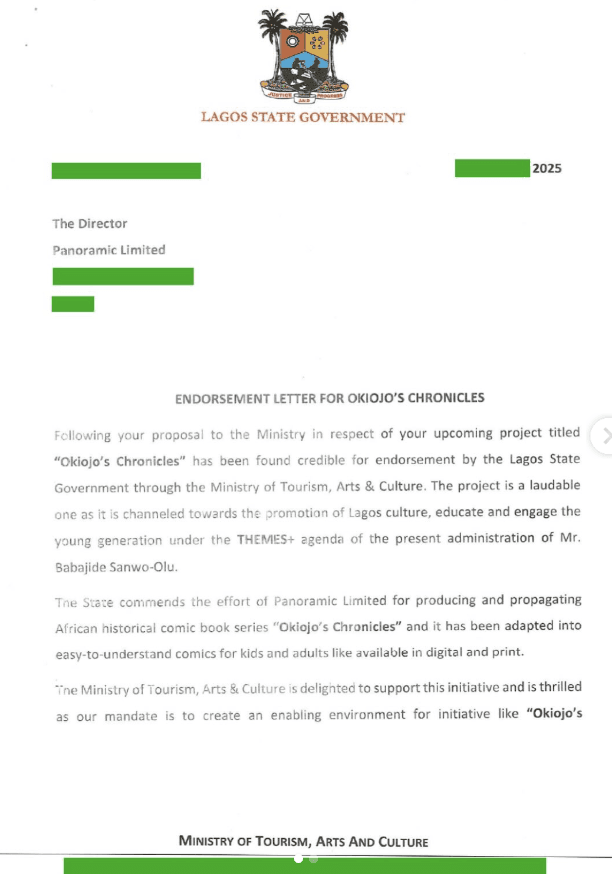

Although it has not gone entirely unnoticed locally, with the Lagos State Government endorsing Okiojo’s Chronicles as a culturally relevant educational project in 2025, the implication was subtle but significant. Sometimes the work is recognised abroad not because it is exotic, but because it fills a gap local systems have not yet learned to value.

Technology as Participation, Not Escape

It was from this place, not from hype, but from curiosity, that Panaramic eventually explored emerging technologies.

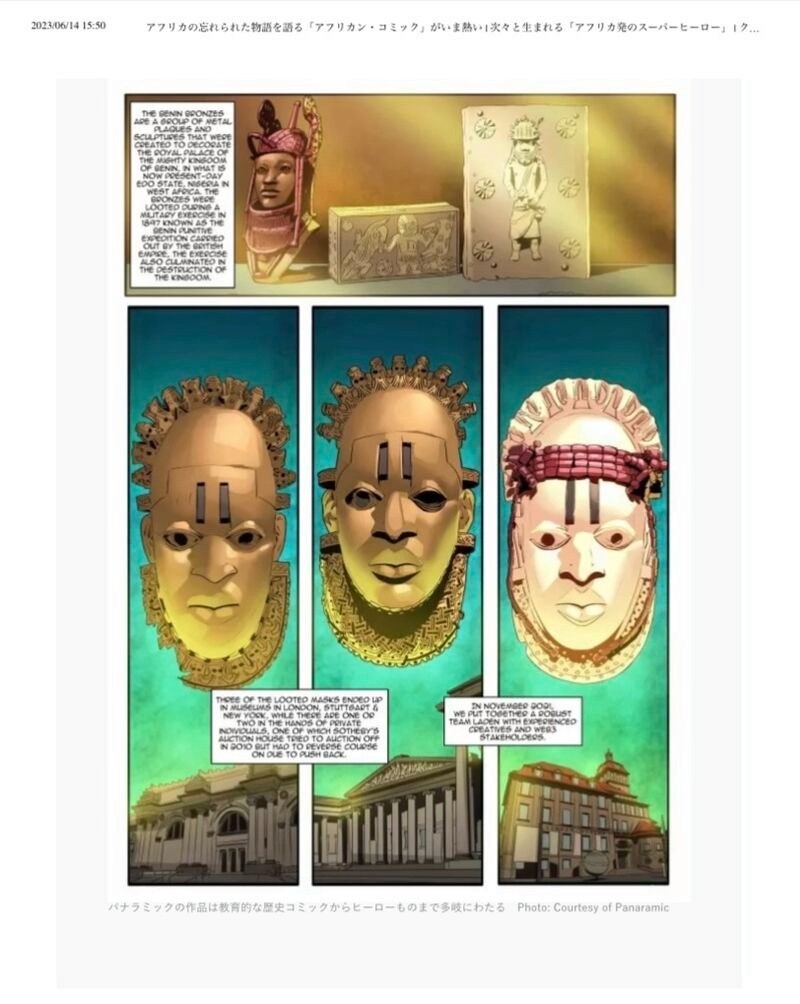

When the studio experimented with NFTs, it did so at a time when the space was dominated by speculation and quick exits. Panaramic’s approach was markedly different.

“We didn’t make the NFT to cash out,” Tunji says. “We made it to say something.”

That ‘something’ centred on ownership, restitution, and narrative control — questions deeply entangled with Africa’s historical relationship to archives and cultural extraction. The project did not deliver overnight wealth or viral success, but Tunji does not measure its value in those terms.

“We may not have made millions from it,” he reflects, “but we played a role.”

Participation, for him, mattered more than profit. Being present in the conversation, even imperfectly, was part of the long game.

Thinking Beyond the Moment

Throughout the conversation, Tunji returns to one recurring concern: legacy. Not legacy as personal acclaim, but as systemic endurance.

“There is nothing more powerful than a good story,” he says. “It is the most powerful influence ever created.”

For Tunji, storytelling is not a soft pursuit. It is nation-shaping work; slow, cumulative, and often invisible until its absence becomes painfully clear. Comics, books, and archives do not announce themselves loudly, but they shape how societies remember, imagine, and repeat themselves.

As Nigeria’s creative industries continue to expand outward, Tunji Anjorin’s work poses a quieter, more uncomfortable question: are we building cultural systems that can outlast trends, or are we simply reacting to the moment?

The answer, if Panaramic’s journey is any indication, lies not in speed, but in staying power.

The Full Conversation

Editor’s note: In late December 2025, we had a chat with the founder. This interview is presented largely as it happened. Apart from light formatting for readability (speaker labels and paragraph breaks), the conversation has not been tightened or restructured. Pauses, digressions, and informal phrasing have been retained to preserve the natural flow of thought.

TheACE: Tunji, let’s start from the very beginning. How did Panaramic actually start? Not the clean version, the real one.

Tunji Anjorin: Honestly, there was no big master plan. Panaramic didn’t start as this grand vision of building an empire or anything like that. It was more about survival. You’re doing the work, trying to understand what you’re doing, trying to figure out the market, trying to figure out yourself. At that point, you’re not thinking in decades. You’re thinking, “How do we get through the next few months?”

TheACE: Yet here you are, almost two decades later, still doing comics.

Tunji: Exactly. And that’s the thing people don’t always understand. Longevity is not something you plan upfront. You don’t wake up and say, “I want to do this for twenty years.” You just keep going. Month by month. Then one year becomes five, five becomes ten, and suddenly you realise you’ve been here a long time.

TheACE: What made you stick with comics specifically, especially in Nigeria where the ecosystem hasn’t always been friendly?

Tunji: Because comics are not trends. Comics are infrastructure. People like trends because they’re exciting. Infrastructure is boring. But infrastructure is what keeps things alive. If you don’t have books, if you don’t have comic books, you don’t have unlimited firewood to keep the fire burning.

TheACE: There’s this popular narrative that Nigerians don’t read.

Tunji: Nigerians read. That narrative is false. The problem is not interest. The problem is access and visibility. If people see the books, they will buy them. But if distribution is poor and books are not visible, people assume there’s no demand.

TheACE: A big part of your work deals with history. You’ve been very clear about how African history is often framed.

Tunji: Yes. We are told African culture starts at the point of enslavement. That is not the truth. When you start the story there, you define everything that comes after through trauma. You erase centuries of history, governance, philosophy, culture — all of that disappears.

TheACE: How do comics help correct or challenge that framing?

Tunji: We’re not trying to tell the full truth of history. That’s not possible. What we’re doing is opening the door. You read a comic, something catches your attention, and then you want to know more. You go and read books. You research. Curiosity is powerful.

TheACE: At some point, Panaramic tried to work with global digital platforms like Comixology.

Tunji: Yes, we did.

TheACE: And it didn’t work out.

Tunji: It didn’t. And it wasn’t because the work wasn’t good. It was about fit. The platform didn’t really know what to do with African historical comics. Their system was built around a different cultural centre. That’s when you realise that these platforms were not designed with you in mind.

TheACE: What did that realisation change for you?

Tunji: It made things clearer. You have two options at that point. You either change your work to fit the system, or you keep building what you believe in. If you keep chasing validation, you’ll lose yourself. Somebody has to build the thing properly.

TheACE: Interestingly, a lot of support for Panaramic came from outside Nigeria.

Tunji: Yes. The diaspora really showed up. We started getting more orders from the US, the UK, places like that. A lot of those readers were not looking for something trendy. They were looking for connection. They wanted stories that helped them understand where they come from.

TheACE: There was also an academic angle.

Tunji: Yes. One of our works was picked up by a college in the United States and added to their curriculum. That was a big moment. It showed that comics are not just entertainment. They can be educational material. This is knowledge. This is culture. And it belongs in serious spaces.

Editor’s note: In November 2023, Grand Valley State University formally acknowledged the use of Panaramic’s comics within World Civilisations courses, with close to 400 students engaging the material since 2021. In 2025, the Lagos State Government also endorsed the comics as culturally relevant educational project.

TheACE: You later experimented with NFTs, which surprised many people.

Tunji: People assumed it was about money. It wasn’t. We didn’t make the NFT to cash out. We made it to say something. It was about ownership, restitution, narrative control. Whether it worked financially or not wasn’t the point.

TheACE: Looking back, do you see that experiment as successful?

Tunji: We may not have made millions, but we played a role. Sometimes being part of the conversation matters more than the outcome. You learn from it. You contribute. Then you move on.

TheACE: You’re also very critical of how Nigeria frames its creative economy.

Tunji: Nigeria cannot survive on music, movies, and fashion alone. Only two fingers cannot do the work of ten. Those sectors are important, but they can’t carry everything. Comics, books, publishing — these things last. They build memory.

TheACE: When you look ahead, what concerns you most?

Tunji: My concern is continuity. Are we building things that will still matter in twenty years? Or are we just reacting to what is popular now? Culture doesn’t survive on moments. It survives on systems.

TheACE: Finally, what does storytelling mean to you, personally?

Tunji: There is nothing more powerful than a good story. It is the most powerful influence ever created. Stories shape how people see themselves and how they imagine the future.

Edited by Mujeeb Jummah

--------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------

AI Use at TheACE

TheACE uses artificial intelligence tools to support research, drafting and analysis across Africa’s creative industries. All content is verified, edited and approved by our human editorial team to ensure accuracy, clarity and responsible storytelling. AI assists our work; it does not replace human judgment.